WILL DEVELOPMENT DESTROY LADAKH?: LIFE & LEISURE

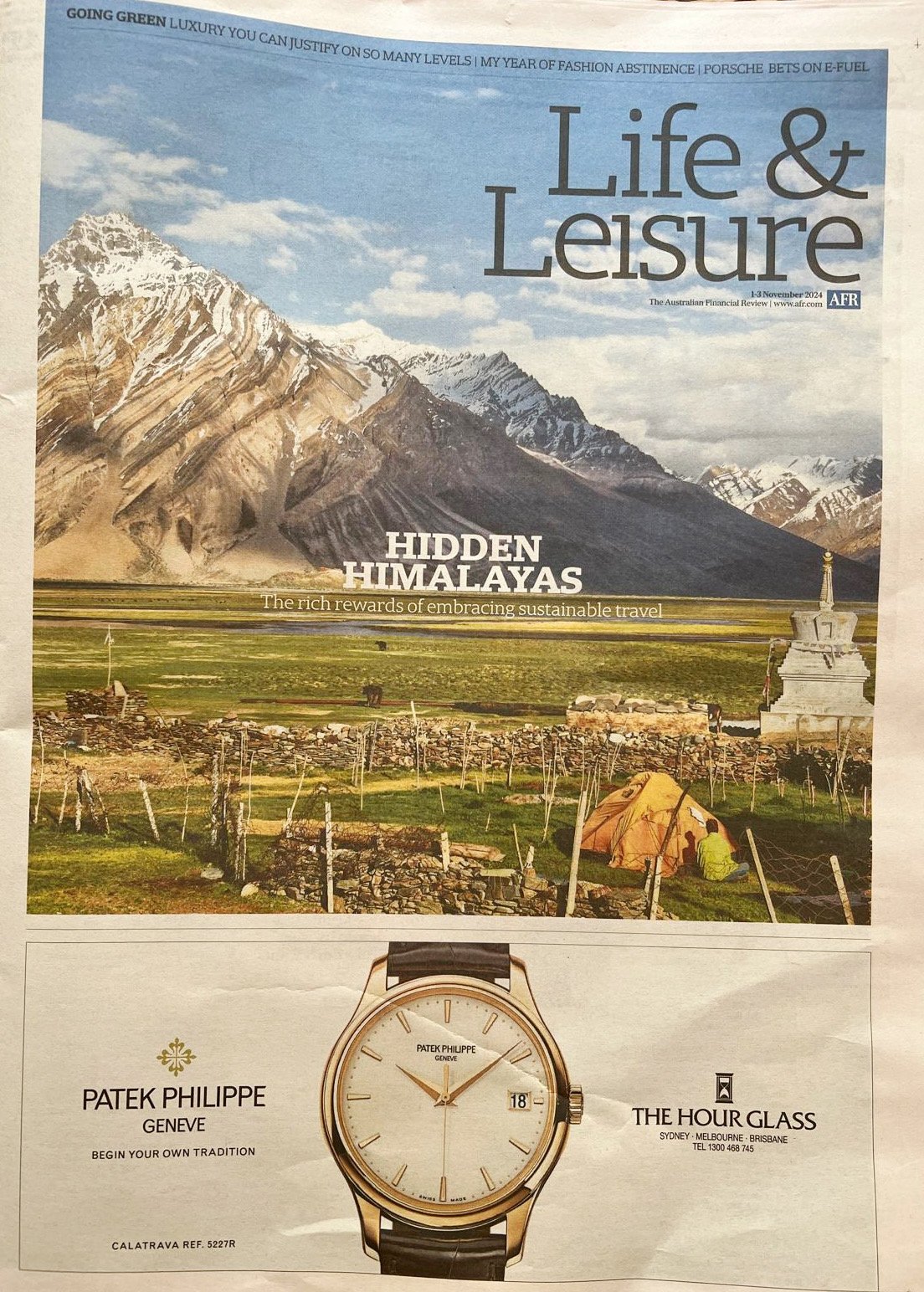

In Ladakh’s fabled Zanskar Valley, remote villages, dramatic landscapes and ancient monasteries await adventurers. But will a new highway destroy the remote culture drawing visitors to the region?The late afternoon sun is setting the fields of Yougar village ablaze, as my husband and I wash the day’s grime from our faces in a glacial stream. The journey to this remote corner of Ladakh’s Zanskar Valley, 3900 metres up on the Tibetan Plateau in northern India, has been one of the most arduous of my life. But this moment, watching the sun tuck itself behind the 12th-century Phugtal Monastery clinging to the opposite cliff, has made every hair-raising minute worth it.

The fact that Zanskar is one of the most inaccessible valleys on Earth is one of its main appeals. In its more remote corners, intrepid travellers can still witness life being lived just as it was a century ago. This afternoon, we were transported back in time as we watched a yak being milked for our tea, dung being stacked atop mud-brick houses to burn over winter when temperatures can drop to minus 40 degrees, and locals using scythes to harvest buckwheat, barley and other crops that have been grown in this region for centuries.

Times, however, are changing in Zanskar, as they are throughout Ladakh. Since Ladakh becoming a union territory in 2019 - separate from Jammu and Kashmir - and the end of pandemic lockdowns, visitor numbers have been growing by 30 percent annually. On the 10-hour drive from Ladakh’s capital, Leh, along the unfinished Leh-Zanskar highway zigzagging across the Zanskar Range, we were often stopped by earth-moving trucks tracing furrows in the land.

Once completed next year, this highway will significantly reduce travel time for travellers. It will also make Zanskar, often cut off from the rest of Ladakh for months in winter, accessible year-round. As a result, tourism, trade and development to the valley are set to be significantly boosted.

Here in Yougar, access remains limited to those willing to risk a 90-minute hike along a foot-wide dirt path carved into a cliff high above the Zanskar River. The highway will soon reach this place, too, however. That’s good news for my nervous system. It’s likely bad news, though, for this village of just six houses and the peaceful, agrarian way of life of its inhabitants and the rich culture they have amassed over centuries.

Once night falls, my husband and I sit on the kitchen floor of our mud-brick homestay with the owner’s four grown children as they prepare momos (dumplings) for dinner. We talk about daily life in Yougar, and the importance of growing indigenous crops, especially at a time when an estimated 75 percent of crop genetic diversity has been lost globally. At one point the son, in his early 20s, says he is excited about being able to sell the vegetables he grows once cars can reach Yougar. It’s hard not to feel that something far more valuable will be lost, however, once he can.

Increased access to this region and the changes it is bringing is preoccupying many Zanskaris. Next day we drive to a nunnery in Zangla, another remote village and former royal seat dotted with whitewashed stupas and crumbling mud-brick houses strung with tattered prayer flags. Zangla Nunnery, believed to have existed since medieval times, is home to 26 nuns who have dedicated their lives to preserving Buddhist teachings.

An elderly nun in burgundy robes ushers us into a prayer room filled with murals and statues of ancient deities. Because of the changing pace of life in Ladakh, she tells us, even nuns now don’t have enough time.

“We used to do puja (ceremony) all day in winter, and in summer we were always playing, we were very happy here,” she says, with a sweep of her hand. “Now we have better facilities - kitchen, bathrooms, guesthouse - but we don’t have time like that.”

Later, in the kitchen of our simple Guru View homestay on the outskirts of Padum, the largest town in Zanskar and a hub for trekkers, we help make noodles for a Tibetan thukpa stew. The owner, Sherab, who has spent the afternoon tending the large vegetable garden in front of her house, explains how agriculture and pastoralism are being left behind in Zanskar. As locals engage more in tourism-based businesses such as homestays and trekking companies, tourists’ needs are being prioritised over local customs.

This is all too evident as we walk through Padum. Menus are largely full of western foods, mud-brick houses are falling into ruin and being cut in half to make way for the widened highway, young people are clad in cheap faux-branded clothes, and homogenised concrete and aluminium guesthouses are being constructed faster than the wind whipping across the Himalayan plateau.

But while the world’s problems are amplified here in Ladakh, so are the potential solutions. Before heading to Zanskar, we stayed at Dolkhar Ladakh, a boutique hotel in Leh that's championing a movement resisting globalisation in the region.

Our villa was constructed almost entirely from natural materials that have been used in Ladakh for centuries, including compressed earth and slate walls, and ceilings made from local willow and poplar wood. More than 40 local craftspeople handwove the hotel’s rugs, throws and cushions from homespun sheep and yak wool. The menu at its restaurant, Tsas, features native ingredients including pigeon peas, buckwheat and yak cheese, all sourced from neighbouring villages.

“The rate of development has been so fast that Ladakh has gone straight into fire fighting, catering to whatever demand comes,” said 33-year-old owner Rigzin Lachic, who built Dolkhar on an apricot and apple orchard that belonged to her grandmother. “I’m trying to fight against that, by looking to the past to reimagine Ladakh’s future.”

As our days in Leh unfold, we discover an increasing number of businesses doing the same thing. We have an exquisite dinner at Namza Dining, a restaurant reviving forgotten Ladakhi dishes; shop at Lehvallée, run by two Ladakhi sisters who offer naturally dyed pashmina shawls handwoven by local artisans; and meet the owner of Siachen Naturals, a natural food company that is bolstering traditional food practices by stocking organic indigenous foods including barley-based soups and porridges packed with local herbs.

Reflecting on the inevitable changes at hand in Ladakh, the Buddhist concept of impermanence comes to mind. The world is in a constant state of flux. Ideally, that change strengthens cultures and ecosystems, rather than degrading or homogenising them. Perhaps in response to Ladakh’s transformation, farming, natural building and artisanship will become aspirational for more young Ladakhis so they can enhance what makes their region special, before it’s too late.

NEED TO KNOW

Dolkhar Ladakh | from $260 (Rs15,000) a night including breakfast. Day trips, which can include heritage village walks, pottery and metal craft experiences and cooking classes, are extra.

When to visit | Ladakh’s high season is May to September. Visit during winter (October to February) for festivals, optimal snow leopard spotting, and fewer crowds.

Getting there | Air India flies daily from Sydney and Melbourne to Leh, via Delhi. Zanskar is currently a 10-hour Jeep drive from Leh.

This article was first published in print and online here.