Kimberley Coast: SMH TRAVELLER

Immersing yourself in this ancient land is like standing on the edge of time itself, writes Nina Karnikowski.

Leaning back in our inflatable Zodiac on WA’s Kimberley coast, we watch hundreds of seabirds - cormorants and frigatebirds, terns and curlews, boobies and noddies - wheel across the empty blue sky.

I grab mum’s hand, my companion for this seven-day APT expedition cruise, and squeeze. She’d been nervous about her first post-Covid trip. But exploring the world’s longest stretch of undefiled coastline, on a small ship cruise led by a 10-strong expedition team of naturalists, ecologists and marine biologists, seemed like the perfect re-entrance into the travel world. As we watch the bird’s gentle ballet and listen to their gentle caws, I know mum’s feeling the same as me: if we had wings, we’d be soaring too.

As our Zodiac continues circling Adele Island, one of 2,500 islands scattered along this 12,800-kilometre stretch of coast, we learn that we’re floating above a huge lagoon that’s a feeding and breeding ground for humpback whales, rays and green turtles. The island, we’re told, was declared a nature reserve in 2001, since it’s also a critical habitat for the thousands of seabirds that use the protective grasses covering the island to build nests and raise chicks in.

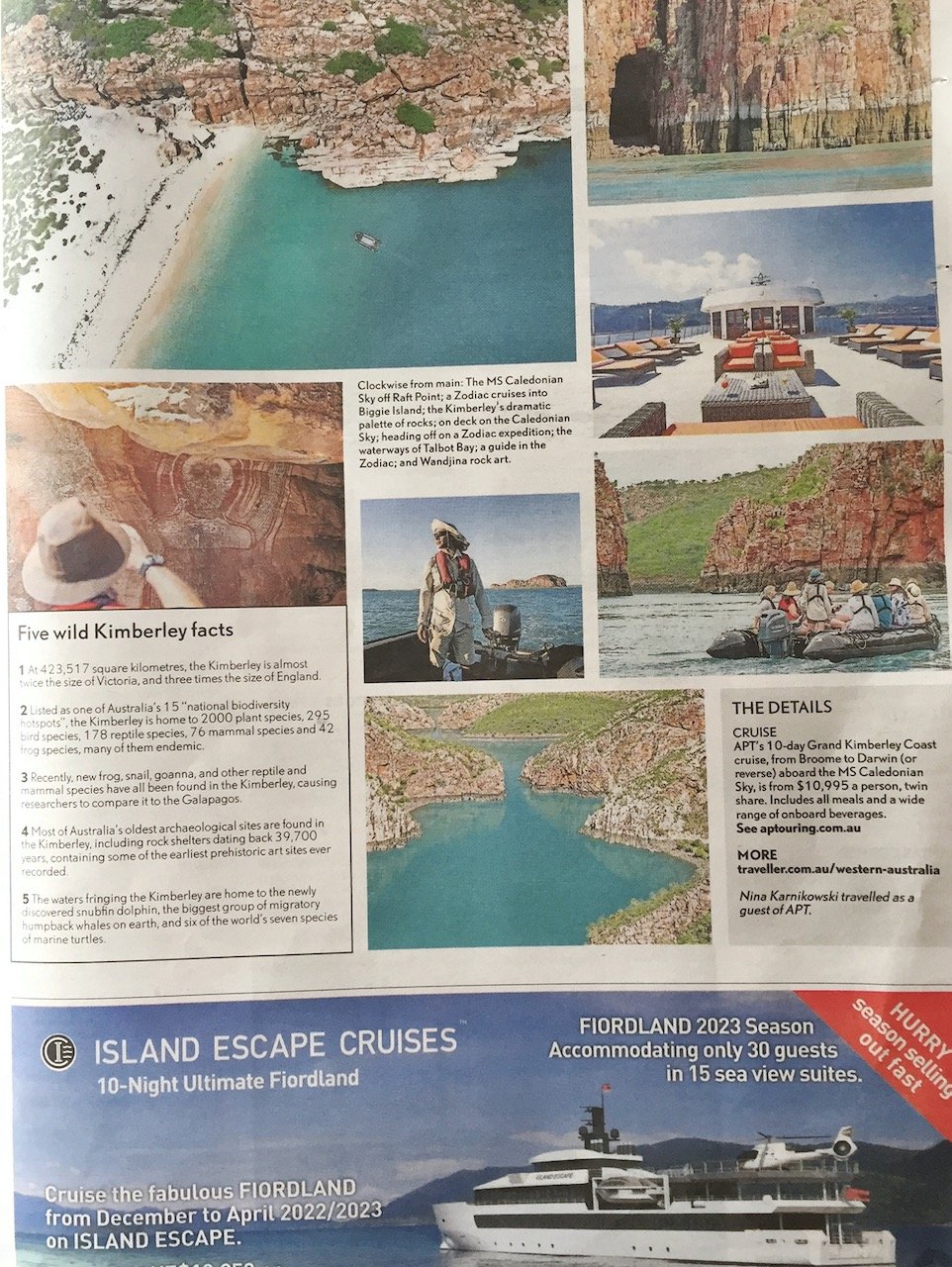

We soon arrive back at our ‘nest’, APT’s own Caledonian Sky, where we’re welcomed with chilled refresher towels and cold glasses of juice. The ship is small in cruise terms, carrying a maximum of 99 guests, which means we can slip into areas other ships can’t. The size also lends the ship an air of nostalgia, only enhanced by its gleaming wood-panelled walls, and mum and I slip 70 years back in time while watching the day’s last light ooze over the ocean from the balcony of our deluxe suite.

It’s in Talbot Bay, the following day, that the almost planetary proportion of the Kimberley hits me. After a sun-drenched lunch on the outdoor deck while watching the furthest reaches of the Australian mainland slide by, we head back out in the Zodiacs.

“This is one of the world’s last true wildernesses,” says our guide, a young marine biologist named Kieran Buckley, as we putter around the bay. “A lot of it is either national park or managed by Indigenous communities, so it’s 98 percent untouched.”

It certainly looks untouched as we weave around dramatic sedimentary sandstone formations that look like ancient ruined cities, painted deep oranges, greys and whites from leaching minerals. Around 1.8 billion years ago, says Kieran, the Kimberley was a separate land mass that collided with the ancient Pilbara and Yilgarn regions, forming the core of the Australian continent – a fact that leaves me feeling as though I’m standing on the edge of time itself.

Kieran points to the mountains towering around us, and interlaces his fingers to explain how they are the remnants of the collision. “The crumpled layers of these mountains tell us about the shaping of Australia, and how it has been carved out over billions of years by wind and water.”

Speaking of water, we’re desperate to swim, but Kieran says the sea below us is teeming with saltwater crocodiles. “But don’t worry,” he says with a grin, “you’re about to get wet anyway.”

And with that he zooms off towards the Horizontal Waterfalls, described by David Attenborough as “one of the greatest natural wonders of the world”.

We round a corner and suddenly there the falls are, rushing through a narrow gap in the soaring, rust-red McLarty Ranges, like water being sucked down a plughole. The Kimberley is famous for its enormous tides, and here the 10-metre tidal fall pulls up to one million litres every second through the gap, creating a waterfall effect.

“Ready?” asks Kieran. We grab onto a central rope and whoosh over the sideways waterfall, our boat dancing wildly over eddies and whirlpools to the other side. We shriek like kids as the spray spangles us, and I hear mum’s laughter over the rushing falls.

We cruise further up the coast overnight, the slurp of the sea against the side of the ship lulling us to sleep, and the following morning visit another extraordinary natural phenomenon at a place called Doubtful Bay.

Covering over 400 square kilometres, Montgomery Reef is Australia’s largest inshore reef that, thanks to the Kimberley’s massive tides, rises up out of the ocean every day.

Our Zodiac draws up alongside the reef as it emerges from the sea, like some gigantic, ancient tortoise, and we watch hundreds of waterfalls pour off the top. A white egret swoops to collect fish caught in the pooling water, and a green sea turtle scuttles across the exposed reef to the ocean, joining dozens more turtles popping their gleaming heads up all around us.

While coral reefs the world over are facing an uncertain future because of rising water temperatures, Montgomery is thriving. “This reef can handle temperature and environment change, because it happens every day when it comes out of the water,” says our guide. “Scientists are actually taking coral from this reef and planting it on the Great Barrier Reef, to see how it goes.”

I catch mum’s eye and smile. I know she worries about the world her grandchildren are inheriting. But this tale of Montgomery’s resilience brings with it hope for the future of the planet, and a renewed desire to help conserve and steward it.

When it comes to land stewardship, there are no more important voices to listen to than those of Indigenous communities. On our final day, we head to Freshwater Cove, or Wijingarra, where we meet Naomi Peters, a young woman from the Worrora tribe. Freshwater Cove is so remote you can only access it by boat or helicopter, and Naomi will stay here with just a few family members for more than half the year, welcoming passing tourists through her family’s company Wijingarra Tours.

After being welcomed to country with an ochre and smoking ceremony, Naomi tells us that after being nearly wiped out as a people and forced to live in town, she is proud that she and her family are back on country. She’s proud that they’re running this small business on land her people have inhabited for tens of thousands of years. And she’s proud to be continuing the work of her mother, Isobel Peters, who spearheaded whale conservation in this region through the Arraluli Whale Sanctuary Project.

“We’re trying to educate people on preserving what we have left here,” says Naomi, motioning to the trees, the ocean, the land, all of which she describes having a deep spiritual connection to.

Naomi’s brother Neil walks us up into the hills above the cove, passing lilac morning glories, golden bottlebrush and wattle, our feet crunching along the dry earth, and ushers us into an open-sided cave. The Kimberley has the greatest diversity and frequency of rock art in Australia, and this cave is adorned with art in the Wandjina style, dating back up to 4,000 years.

Wandjina art depicts powerful ancestral beings who created the land and everything in it, and who offer guidance to the people of the Kimberley, making this small cave feel like a cathedral. Neil points out a giant stingray, a dragonfly, and a stunning circular design that tells the story of a boy who ignored his mother’s advice and headed out onto a reef where he drowned. “Some of these are sad stories,” says Neil quietly, “but they’re always about learning. Don’t rush in life, wait your turn, learn to listen.”

And it’s this, really, that the untameable Kimberley coast offers any curious traveller: the invitation to learn to listen again, so you can hear the song of the earth.

Nina Karnikowski travelled as a guest of APT

FIVE WILD KIMBERLEY FACTS

At 423,517 square kilometres, the Kimberley is almost twice the size of Victoria, and three times the size of England.

Listed as one of Australia’s 15 ‘national biodiversity hotspots’, the Kimberley is home to 2000 plant species, 295 bird species, 178 reptile species, 76 mammal species and 42 frog species, many of them endemic.

Recently, new frog, snail, goanna, other reptile and mammal species have all been found in the Kimberley, causing researchers to compare it to the Galapagos.

Most of Australia’s oldest archaeological sites are found in the Kimberley, including rock shelters dating back 39,700 years, containing some of the earliest prehistoric art sites ever recorded.

The waters fringing the Kimberley are home to the newly discovered snubfin dolphin, the biggest group of migratory humpback whales on earth, and six of the world’s seven species of marine turtles.

This story first appeared in print and online here