rewilding in india: LIFE+LEISURE

A Rajasthani safari camp founded by an entrepreneurial conservationist is working with the community to boost the local leopard population.It’s late afternoon when we arrive at Jawai, in the Godwar region of south-western Rajasthan, and the area is a hive of activity. Wearing saffron-coloured turbans, white dhoti loincloths and with elaborately curled moustaches, local Rabari tribesmen whiz by on motorbikes.

Farmers encourage their buffalo along dirt tracks lined with euphorbia cactus and yellow-flowered Senna trees, while village women balancing towering bundles of grasses on their heads walk through the honey-coloured afternoon light.

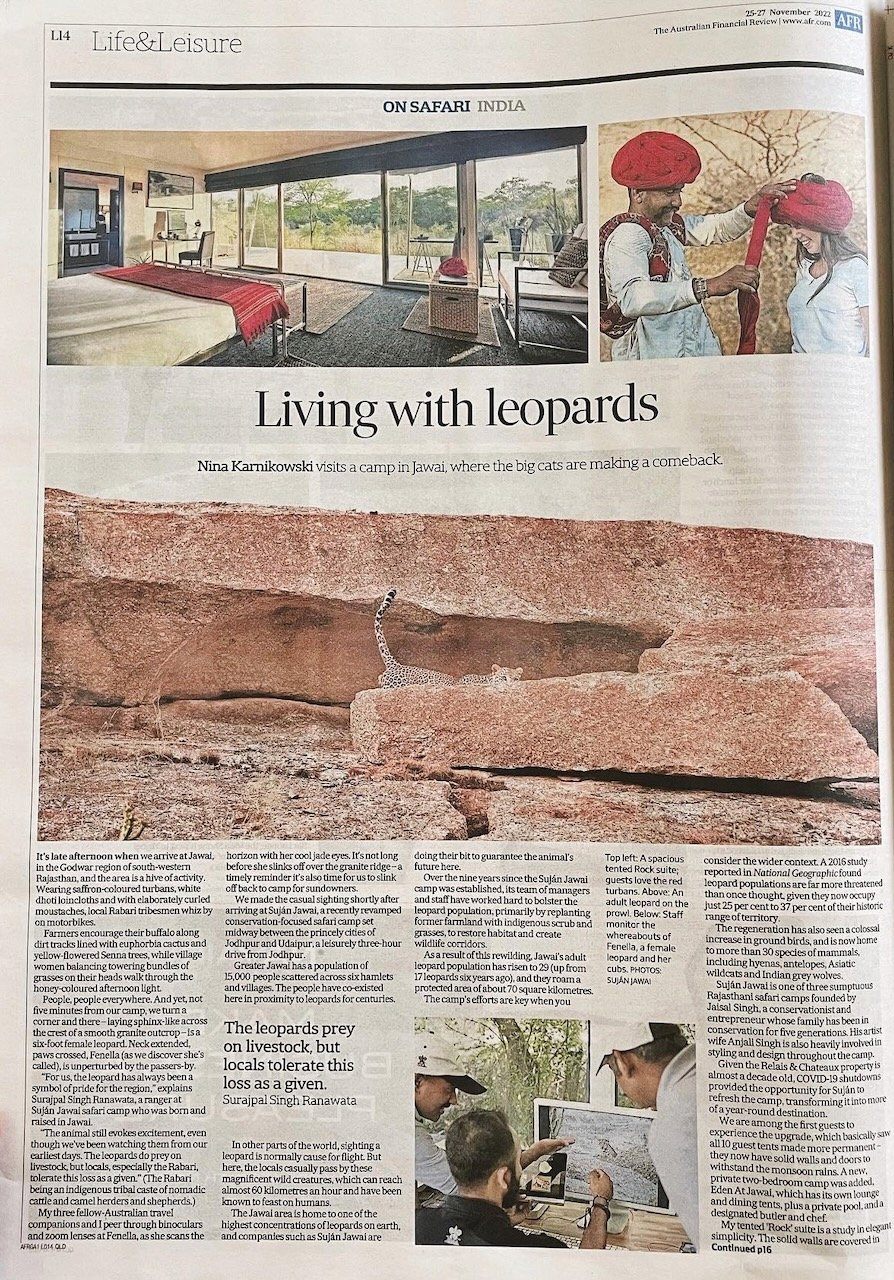

People, people everywhere. And yet, not five minutes from our camp, we turn a corner and there - laying sphinx-like across the crest of a smooth granite outcrop - is a six-foot female leopard. Neck extended, paws crossed, Fenella (as we discover she’s called), is unperturbed by the passers-by.

”For us, the leopard has always been a symbol of pride for the region,” explains Surjapal Singh Ranawata, a ranger at Suján Jawai safari camp who was born and raised in Jawai.

”The animal still evokes excitement, even though we’ve been watching them from our earliest days. The leopards do prey on livestock, but locals, especially the Rabari, tolerate this loss as a given.” (The Rabari being an indigenous tribal caste of nomadic cattle and camel herders and shepherds.)

My three fellow-Australian travel companions and I peer through binoculars and zoom lenses at Fenella, as she scans the horizon with her cool jade eyes. It’s not long before she slinks off over the granite ridge - a timely reminder it’s also time for us to slink off back to camp for sundowners.

We made the casual sighting shortly after arriving at Suján Jawai, a recently revamped conservation-focused safari camp set midway between the princely cities of Jodhpur and Udaipur, a leisurely three-hour drive from Jodhpur.

Greater Jawai has a population of 15,000 people scattered across six hamlets and villages. The people have co-existed here in proximity to leopards for centuries.

In other parts of the world, sighting a leopard is normally cause for flight. But here, the locals casually pass by these magnificent wild creatures, which can reach almost 60 kilometres an hour and have been known to feast on humans.

The Jawai area is home to one of the highest concentrations of leopards on earth, and companies such as Suján Jawai are doing their bit to guarantee the animal’s future here.

Over the nine years since the Suján Jawai camp was established, its team of managers and staff have worked hard to bolster the leopard population, primarily by replanting former farmland with indigenous scrub and grasses, to restore habitat and create wildlife corridors.

As a result of this rewilding, Jawai’s adult leopard population has risen to 29 (up from 17 leopards six years ago) and they roam a protected area of about 70 square kilometres.

The camp’s efforts are key when you consider the wider context. A 2016 study reported in National Geographic found leopard populations are far more threatened than once thought, given they now occupy just 25 per cent to 37 per cent of their historic range of territory.

The regeneration has also seen a colossal increase in ground birds, and is now home to more than 30 species of mammals, including hyenas, antelopes, Asiatic wildcats and Indian grey wolves.

Suján Jawai is one of three sumptuous Rajasthani safari camps founded by Jaisal Singh, a conservationist and entrepreneur whose family has been in conservation for five generations. His artist wife Anjali Singh is also heavily involved in styling and design throughout the camp.

Given the Relais & Chateaux property is almost a decade old, COVID-19 shutdowns provided the opportunity for Suján to refresh the camp, transforming it into more of a year-round destination.

We are among the first guests to experience the upgrade, which basically saw all 10 guest tents made more permanent - they now have solid walls and doors to withstand monsoon rains. A new, private two-bedroom camp was added, Eden At Jawai, which has its own lounge and dining tents, plus a private pool, and a designated butler and chef.

My tented ‘Rock’ suite is a study in elegant simplicity. The solid walls are covered in padded white cotton, decorated with black and white prints of leopards. Textured black jute carpet covers the floor, while scattered scarlet throws and pillows inspired by the Rabari’s bright red turbans provide a colour pop.

Everything, I’m told, has been made in-house under Anjali’s direction, from the chairs and the side tables, to the textiles and artworks. There’s a rain shower and large bathtub in the bathroom. Pass through the sliding glass doors onto the deck, and you’ll discover a writing desk set with pens and paper, and a pouch of watercolours, should inspiration strike. At some point, it might.

But for now, I’m ready for that sundowner. I follow bush tracks lined with head-high post-monsoon grasses to a duo of open-sided mess tents, home to the bar and dining tents - more elaborate versions of my guest suite that open out onto a central courtyard and lap pool.

With an ice-cold gin and tonic from the well-stocked bar to hand, I wander out through billowy white curtains to the courtyard. As the sun drops behind the Aravalli hills, one of the oldest mountain ranges in India, a staff member carefully places flickering lanterns around the courtyard, and hangs them in the surrounding neem trees.

We’re soon met by Yusuf Ansari, Suján's vice-president and director of wildlife experiences, clad in a belted safari jacket and with a moustache that’s as well curled as his British accent is polished.

We gather around a long table under the stars, for a traditional Rajasthani dinner made mostly from food grown in Jawai’s organic kitchen gardens, and on the neighbouring farms.

Over the meal, Ansari - a self-described ‘Mowgli’ who grew up in Ranthambore National Park - tells us more about the conservation work going on here.

Guests at Suján Jawai automatically provide a ‘conservation contribution’ in the form of $US25 ($37) per person, per night that’s turned over to conservation activities, such as replanting indigenous scrub and grasses, opening up caves and den sites that had been blocked by farmers, and employing field guides to patrol for poachers.

Suján has also created various community development initiatives, including funding five schools and starting a free mobile medical unit. Aside from supporting local communities, these services ‘make protection of wildlife habitats and species an economic incentive for local communities’, Ansari says.

In other words, the more jobs Suján provides for the community, and the more services they offer them, the more invested residents will be in protecting the area’s precious flora and fauna.

Early next morning, we head out in a customised safari jeep to see the results of these efforts, the crescent moon and stars still bright in the sky.

As we bump along dusty roads, Ansari gestures to the forest, explaining it took two years of rewilding before life started to return. “Less than a decade ago, this was all under the plough, you never saw a leopard here,” he says, raising his voice over a thrumming chorus of insects, a sure sign of a thriving ecosystem.

As the sun rises, we pass a small white temple dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva. Along with the 300 temples and shrines just like it scattered throughout the Jawai region, it’s key to conservation. “The leopard is not a sacred animal in Hinduism, but because they are around these temples and shrines, the locals associate them with sacredness and they get a layer of protection,” Ansari explains.

The loss of a goat or sheep is therefore seen as an offering to the gods and the community doesn’t take revenge, a perspective that has helped the leopard population increase.

This respectful human/wildlife relationship means is that you see things here that you don’t see anywhere else. “Science tells us leopards are solitary, yet in 2015 we had 16 living on the same hill, and four adults sharing the bringing up of cubs,” says Ansari as we continue driving along a winding sand river-bed.

“This has never been documented in any scientific study about leopards anywhere else in the world. And there's no logical biological explanation for it, except that the leopards have learned to coexist, knowing that, ‘we've got this village down there, there's no hope of survival if we don't get along. So why don't we carve out small patches on this hill, and just be nice to each other?’”

As if on cue, a message crackles through the radio that there’s a leopard nearby.

We zoom off on a ‘Ferrari safari’ to the top of the hill. Behind us is the Jawai bandh, or dam, created in 1946 to supply water to Jodhpur. It’s now a safe haven for migratory birds, including cranes from Siberia and flamingos from the western deserts.

But the real show is in front of us: Two of Fenella’s cubs lazing in the sunshine, barely giving us a second glance.

It’s a much smaller thing, though, that brings the benefits conservation home.

At some point I look down beside the jeep to see an ashy-crowned sparrow-lark, about seven centimetres tall, tending to its egg-filled nest hidden in a tuft of grass, sprouting from a crack in the granite.

I point it out to Ansari, who pauses before responding. “That one lone clump of grass provides all that life support.

If you multiply that by all of this,” he says, stretching his arms wide to take in the landscape before us, “it’s a huge potential for regeneration.”

The writer travelled courtesy of Qantas and Banyan Tours.

Need to Know

Suján Jawai There are six Tented Rock Suites, a Family Felidae Suite, Eden at Jawai (their private camp) and the Royal Panthera Suite, each with private decks that look out over the surrounding wilderness.

Rates Start from $1,200 in summer, $1,760 in high season, and $1,910 in the festive season.

Inclusions Meals, laundry, WiFi, and two daily wilderness drives. Beverages, spa treatments and extra activities cost extra. See thesujanlife.com

Fly there Qantas flies non-stop from Sydney to Bengaluru four times a week, then connects to Jodhpur, through codeshare partner IndiGo. Sujan Jawai is a three-hour drive from Jodhpur. See qantas.com

Touring Banyan Tours is a luxury India travel specialist that plans and operates bespoke India journeys. See banyantours.com

This story first appeared online here and in print below.