MINDFULLY DOES IT: SMH TRAVELLER

nothing could be more urgent than slowing down and properly appreciating both our lives and our planet, WRITES NINA KARNIKOWSKI.It’s Paris, 2017. I’m with 60-something journalists and social media influencers from around the world celebrating the launch of the cultural season for three head-spinning days. I tack a few nights in the Marais on to the end, but still, I’m only just starting to recover from the flight over when I begin the 24-hour journey home.

Can I tell you details about what I did or saw on that trip? Barely. There was a 30-minute swirl around the Louvre and lunch at the Alain Ducasse restaurant at Versailles somewhere in there; a Cy Twombley exhibition (I think) at the Centre Pompidou and a cocktail party at the Paris Opera. All very fancy, but it was so fast and furious that none of it really impacted me in any meaningful way. I returned home feeling kind of empty, wondering if it had been worth the days of jet lagged hell on the other side.

This, however, was in ‘the before’. Before I visited the ‘polar bear capital of the world’ in 2019, a place called Churchill in the Canadian Arctic. There, I watched polar bears paddling through turquoise waters just metres from our boat, and learnt about the detrimental impact our consumptive behaviours, including flying, were having on the bears and our planet. The bears had no way of protecting themselves from the melting of the Arctic ice due to global warming, I understood on that trip. Only our human actions would have an effect.

I returned home filled with questions about how I could do better. I decided to stop travelling with the speed and frequency I had been, and set to work discovering how I, and indeed all of us, could start travelling in a way that was more connected - to ourselves, to the communities we were visiting, and to the natural world.

Because while the travel industry is responsible for about eight percent of the world’s carbon emissions, as well as degraded wilderness areas, over-touristed towns, the erosion of local cultures and more, it also accounts for one in 10 jobs worldwide. It teaches us tolerance and broadens our worldviews. And, when done the right way - ‘right’, to my mind, meaning slower and more mindful - it can be a truly vital, life-affirming force.

In ‘the before’, when I was taking upwards of 10 overseas trips a year, I wanted to be far away, all the time, the more remote the destination the better but really, anywhere was great because it was the movement that mattered. That itchy, dissatisfied, surely-there’s-somewhere-better-just-around-the-corner feeling that had me burning upwards of 40 tonnes of carbon each year on air travel alone (to put that in perspective, the average Australian household has an annual footprint of about 15 to 20 tonnes a year in total), followed me everywhere.

When I stopped moving so fast, though, and my adventures became less frequent and slower, I realised the truth behind Henry David Thoreau’s words: “it matters not where or how far you travel, but how much alive you are.”

Camping trips to nearby national parks or getaways to local beach shacks started to deliver the same level of soul nourishment far-flung trips would have once had, simply because I was framing them differently. They were lowering my carbon footprint, yes, and helping me build a closer relationship with home, but they were also giving me a chance to widen my aperture for awe.

By slowing down and paying more attention, things I once would have perceived as ordinary - wallabies bouncing through bushland, say, or flannel flowers nodding their heads by a river - were becoming anything but. As it turns out, destinations are only as rich as the attention we bring to them. Which means we don’t have to go far at all to experience life with a sense of adventure and openness. It all just depends on our state of mind and the way we perceive things.

Aside from expanding our ideas of what journeys can be, mindful travel is also about harking back to an older, slower way of travelling. To a time when holidays were longer because they were less frequent and we were less busy, and when we remembered what a privilege travel really is.

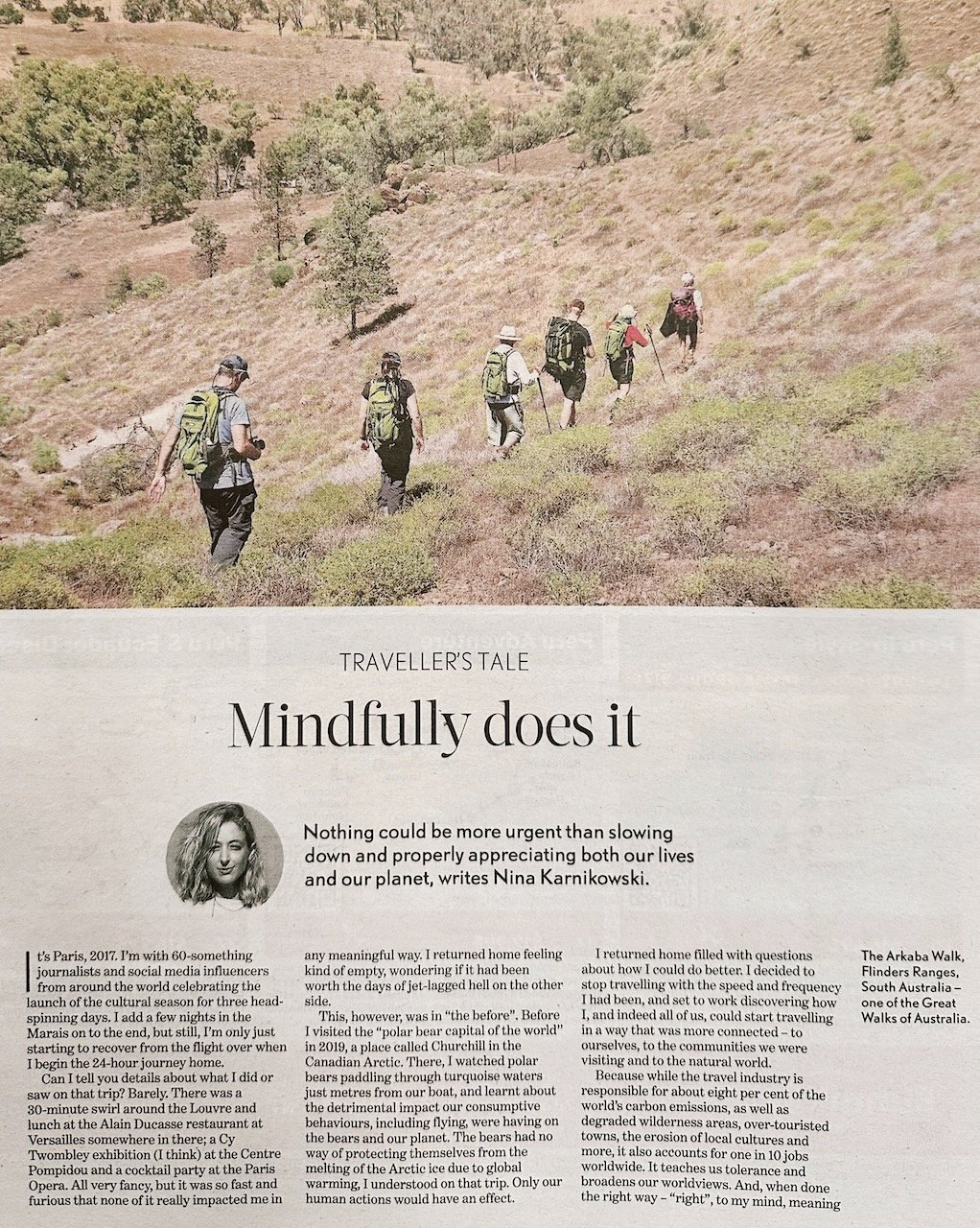

Compare that trip to Paris to the four-day Arkaba Walk I recently did in South Australia, where I hiked across a spectacular rewilded 60,000-acre former sheep station, stopping at swag camps along the way where showers were limited to the amount of water that could fit in a single bucket. It was a slow journey that left swathes of time to connect to nature, and that contributed to nature conservation. It left me feeling exalted at the end of each day and, as our guide said, was a reminder that, “we are all born with wilderness in us, no matter where we’re from, and we’re all trying to reconnect to that.”

Foreign travel will, of course, always be something we desire. It is economically important, accounting for that 10 percent of global jobs, it opens our hearts and minds, and it can be hugely educational. There are measures we can take to make far-flung trips more environmentally friendly, offsetting carbon or choosing the most direct plane route being just two of them.

Perhaps more important than those, though, is getting clear on the purpose behind each overseas trip, to make them more satisfying, and therefore diminishing the need to go quite so often. Are we going for external reasons, for instance to go to that crowded European city because of the 127 images we’ve seen of it on that social media platform? Or are we going for internal reasons, because we have a personal connection to the place, or because we want to learn something about the ecological or cultural issues it’s facing, or to give back to it in some way?

When our motivations are internal, trips are likely to be far more meaningful and memorable, and can help us be a force for good. Because I travelled to India last year to visit an ethical fashion atelier a friend told me about years earlier, I developed a close relationship with the founder and the more than 100 female artisans she supports that will continue for years to come. It was a trip that connected me deeply to the place and the community that lived there because I left enough time for that connection to be forged, staying for one week rather than popping in for a few hours. It was also heartening to know my travel dollars were going directly to the artisans.

According to the UN’s World Tourism Organisation, 95 percent of money spent by tourists leaks out of host countries and into the hands of multinational corporations. With more mindfulness, though, we can start to change that. By doing a bit more research to make sure we’re staying in locally owned hotels and eating in locally owned restaurants, using local indigenous guides and buying locally made handicrafts, we can keep our powerful travel dollars (and they are very powerful, considering only six percent of the world’s population has ever travelled on a plane) in the pockets of locals.

My biggest realisation about the powers of more mindful travel, though, came when going nowhere at all. In mid-2021 I did a 10-day Vipassana silent meditation retreat, a one-hour drive from my home. I arrived at the retreat centre filled with fear that I’d go mad from the one hundred-plus hours of meditation. But the real madness, I realised when it was all over, is the speed most of us scramble around at, and our resistance to sitting and facing life, just as it is.

We cram so many things into each day, into each trip, to give the illusion that we’re on top of things and that we’re making the most out of life, that we’re barely aware of what we’re doing most of the time. But none of the supposedly urgent things we hurtle through our days attending to could be more urgent than this: slowing down enough to properly appreciate both our lives and the planet we’re living on.

If we protect what we love, then surely this is the most important thing of all.