RECONNECTING TO NATURE IN BHUTAN: LIFE & LEISURE

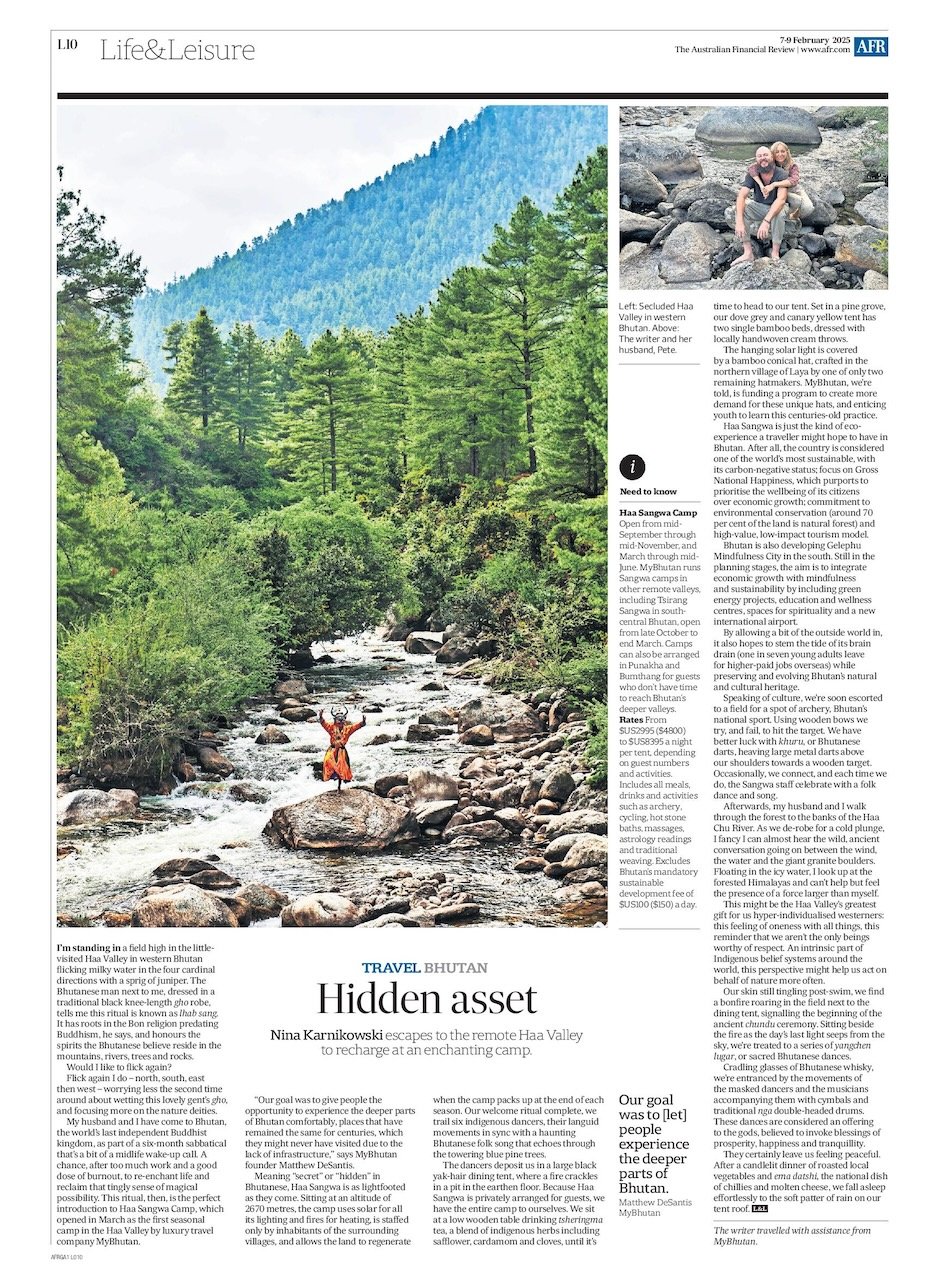

NINA KARNIKOWSKI ESCAPES TO THE REMOTE HAA VALLEY TO RECHARGE AT AN ENCHANTING CAMP.I’m standing in a field high in the little-visited Haa Valley in western Bhutan flicking milky water in the four cardinal directions with a sprig of juniper. The Bhutanese man next to me, dressed in a traditional black knee-length gho robe, tells me this ritual is known as lhab sang. It has roots in the Bon religion predating Buddhism, he says, and honours the spirits the Bhutanese believe reside in the mountains, rivers, trees and rocks.

Would I like to flick again?

Flick again I do – north, south, east then west – worrying less the second time around about wetting this lovely gent’s gho, and focusing more on the nature deities.

My husband and I have come to Bhutan, the world’s last independent Buddhist kingdom, as part of a six-month sabbatical that’s a bit of a midlife wake-up call. A chance, after too much work and a good dose of burnout, to re-enchant life and reclaim that tingly sense of magical possibility. This ritual, then, is the perfect introduction to Haa Sangwa Camp, which opened last year as the first seasonal camp in the Haa Valley by luxury travel company MyBhutan.

“Our goal was to give people the opportunity to experience the deeper parts of Bhutan comfortably, places that have remained the same for centuries, which they might never have visited due to the lack of infrastructure,” says MyBhutan founder Matthew DeSantis.

Meaning “secret” or “hidden” in Bhutanese, Haa Sangwa is as lightfooted as they come. Sitting at an altitude of 2670 metres, the camp uses solar for all its lighting and fires for heating, is staffed only by inhabitants of the surrounding villages, and allows the land to regenerate when the camp packs up at the end of each season.

Our welcome ritual complete, we trail six indigenous dancers, their languid movements in sync with a haunting Bhutanese folk song that echoes through the towering blue pine trees. The dancers deposit us in a large black yak-hair dining tent, where a fire crackles in a pit in the earthen floor. Because Haa Sangwa is privately arranged for guests, we have the entire camp to ourselves. We sit at a low wooden table drinking tsheringmatea, a blend of indigenous herbs including safflower, cardamom and cloves, until it’s time to head to our tent.

Set in a pine grove, our dove grey and canary yellow tent has two single bamboo beds, dressed with locally handwoven cream throws. The hanging solar light is covered by a bamboo conical hat, crafted in the northern village of Laya by one of only two remaining hatmakers. MyBhutan, we’re told, is funding a program to create more demand for these unique hats, and enticing youth to learn this centuries-old practice.

Haa Sangwa is just the kind of eco-experience a traveller might hope to have in Bhutan. After all, the country is considered one of the world’s most sustainable, with its carbon-negative status; focus on Gross National Happiness, which purports to prioritise the wellbeing of its citizens over economic growth; commitment to environmental conservation (around 70 per cent of the land is natural forest) and high-value, low-impact tourism model.

Bhutan is also developing Gelephu Mindfulness City in the south. Still in the planning stages, the aim is to integrate economic growth with mindfulness and sustainability by including green energy projects, education and wellness centres, spaces for spirituality and a new international airport. By allowing a bit of the outside world in, it also hopes to stem the tide of its brain drain (one in seven young adults leave for higher-paid jobs overseas) while preserving and evolving Bhutan’s natural and cultural heritage.

Speaking of culture, we’re soon escorted to a field for a spot of archery, Bhutan’s national sport. Using wooden bows we try, and fail, to hit the target. We have better luck with khuru, or Bhutanese darts, heaving large metal darts above our shoulders towards a wooden target. Occasionally, we connect, and each time we do, the Sangwa staff celebrate with a folk dance and song.

Afterwards, my husband and I walk through the forest to the banks of the Haa Chu River. As we de-robe for a cold plunge, I fancy I can almost hear the wild, ancient conversation going on between the wind, the water and the giant granite boulders. Floating in the icy water, I look up at the forested Himalayas and can’t help but feel the presence of a force larger than myself.

This might be the Haa Valley’s greatest gift for us hyper-individualised westerners: this feeling of oneness with all things, this reminder that we aren’t the only beings worthy of respect. An intrinsic part of Indigenous belief systems around the world, this perspective might help us transform our selfishness, to act on behalf of nature more often.

Our skin still tingling post-swim, we find a bonfire roaring in the field next to the dining tent, signalling the beginning of the ancient chunduceremony. Sitting beside the fire as the day’s last light seeps from the sky, we’re treated to a series of yangchen lugar, or sacred Bhutanese dances.

Cradling glasses of Bhutanese whisky, we’re entranced by the movements of the masked dancers and the musicians accompanying them with cymbals and traditional nga double-headed drums. These dances are considered an offering to the gods, believed to invoke blessings of prosperity, happiness and tranquillity.

They certainly leave us feeling peaceful. After a candlelit dinner of roasted local vegetables and ema datshi, the national dish of chillies and molten cheese, we fall asleep effortlessly to the soft patter of rain on our tent roof.

This article was first published in print and online here.